Adapted from a lecture given by Damian Murphy before a reading of one of the stories from Daughters of Apostasy.

One of the most baffling things about occult fiction is that there’s so little of it. There are endless examples of occult motifs in fiction and literature, but very little fiction that has the esoteric at its heart. Admittedly, my criteria is somewhat stringent—I want to come away from a piece of occult fiction with a deeper understanding than I had before, whether I can articulate that understanding or not. If I want to further my intellectual knowledge, I’ll read an academic study. For a deeper grasp of esoteric principles, a more poetic approach is needed.

The focus of my own work is occult initiation and the range of experiences that arise from it. I feel that the mechanisms involved in this phenomena are so universal to human experience that even readers with no direct interest in these matters can relate to the associated themes. Further, I suspect that people who seek out artistic expression in the underground have something very much in common with those who seek out initiatory gnosis. Both of these things can be represented by the symbol of the underground stream—a source of inestimable wealth that continually renews itself, remains hidden from the eyes of those on the surface, and provides a type of nourishment that can’t be found elsewhere.

My goal with writing is to convey, in as much variety as I can, the experiences of the occult initiate. A direct approach is destined to failure. Occult knowledge is never conveyed directly. Not so much because it’s forbidden to do so, though it often is, but simply because it doesn’t lend itself to conventional modes of expression. I must employ a number of different strategies in order to accomplish my aim, some of which I’ll enumerate here.

Visceral description, in which the sensations of the esoteric practitioner are conveyed in as direct a manner as possible, is the first and most obvious technique. I find it a little too obvious for my tastes, especially if it’s employed in a typical occult context. The experience can be more effectively described in terms of a place, or an intimate encounter, or even an object or series of objects. In ‘The Scourge and the Sanctuary’, for instance, one process in particular is represented by an act of trespass into a sumptuous penthouse apartment. The experiences that arise from this act can be taken, in part, as an analog to those of a similar operation that takes place in a subtler locale. One of the rules I set for myself is to always allow for multiple interpretations. There must always be a human thread that runs throughout my stories. This keeps the reader engaged on a very basic level, avoiding the pitfall of losing their attention in a labyrinth of esoterica.

Misdirection has become a favorite technique. So much so that I use it in almost everything I write. With this approach, the reader is given a clear idea of what to follow while other elements are furtively introduced in the background that are not consciously picked up on. This is often seen in film—the eye is encouraged to focus on the action in the foreground while less obvious cues are used to create a mood, set the atmosphere, or even provide a commentary on the film’s themes. Though these elements aren’t picked up on directly, they affect the way the viewer takes in the film.

With written narrative, this is a little trickier, but still possible. Often, at the outset of a story, I’ll have a particular structure in mind which is concealed from the reader. The story itself might comprise an initiation of one or more characters into the mystery that lies at the heart of that structure. The reader is then made to wander through an environment for which a map exists, but that map largely been withheld from them. In the writing itself, emphasis is put not on the underlying structure, but on the intuitions and sensations of the characters. This allows the mysteries of the story to speak directly to the senses while informing the reader’s awareness on a deeper level as well.

The classic method of representing the initiatory process in fiction is allegory, though I find this to be far too obvious. Robert Aickman was quite fond of subverting this device. He would create an allegory, usually Freudian, and lead the reader to suppose that they’d found the symbolic key to the story, only to suddenly break with the allegory in a very unexpected way, making it impossible to apply any single interpretation. This keeps the reader constantly coming back to the narrative in an attempt to find its true meaning. Once the feeling of having understood has been possessed and then lost again, there’s a certain reluctance to fully let it go. The reader wants their cleverness to count for something, and they’ll be willing to work a little harder to see to it that it does.

These methods tend to work best in combination. Some of them are used simply to get people thinking about what they’ve read in a different way than they’re used to. I aim to invite, to entice, even subtly to trick the reader into engaging with the mysteries of the story on a deeper level than they might otherwise.

A lot of my techniques have been taken from films. The work of Hitchcock contains a seemingly endless supply of tricks that can be adapted to text. The single, uncut long shot is a perfect example. This method tends to convey a sense that the viewer is being shown everything that happened, that the director is not cheating or holding anything back. Hitchcock’s most notorious use of this strategy is found in his film Rope, which consists, in its entirety, of two very long single takes. In a lesser director’s hands, this would never work—a single, hour-long shot would tend to overwhelm the viewer. Hitchcock handles it with such elegance that I didn’t even realize that he’d done this until my second or third viewing of the film, and only then because I’d been told.

The same technique can be used in a written narrative. A story might present a single, long scene in which the action is meticulously followed without letting up. This is especially interesting when the narrative involves invisible forces and visionary passages. Closely following a character’s passage into and back out of the visionary state seems to lend an air of legitimacy to the whole affair.

Stanley Kubrick, in his adaptation of The Shining, constructed a hotel which features an impossible architecture. Were the viewer to carefully observe the characters passing from one place to another in the hotel’s interior and, based on what they’ve been shown, attempt to construct a map of the space, the different sections of the map would fail to line up. The map would contain overlapping spaces, an inconsistent placement of several rooms, and doors leading to places that they logically ought not to. Kubrick was fairly subtle about this, though it’s not too difficult to spot once you know what he’s done. The impression given is that the space itself is definitely suspect, yet the viewer can’t quite put their finger on exactly why or how. Techniques such as this one can be employed to give the impression that there’s more than one level of reality at play. This is very difficult to accomplish in a textual narrative without showing one’s hand, but there are means.

Luis Bunuel is another filmmaker whose works I’ve plundered without remorse. In That Obscure Object of Desire, he cast two different actresses in a single role. He did this to convey that the character in question has two conflicting sides to their personality. In the early scenes, the two actresses are made to look fairly similar, while they progressively diverge as the film goes on.

The trick to using this technique in writing lies largely in the way in which the author imagines the character they want to apply it to. Two distinct personas can be created for a single individual, each of which are pictured differently, have different voices and accents. The two versions of the character might diverge in their motivations and desires while maintaining some overlapping characteristics. To the reader, this can be entirely invisible. I’ve tended, in the instances in which I’ve done this, to reveal just enough to give the impression of two contrary personalities. Once it’s established for the reader, however unconsciously, that a character is divided into two or more different parts, that perception can be used to do all sorts of things. Bunuel went out of his way to make it obvious that the character was played by two different actresses, while I tend to take the opposite approach.

Woody Allen once mentioned, in an interview, an idea for a dramatic film in which a constant stream of comedic elements would play out in the backgrounds of the scenes. Similarly, I once conceived a story penned in the most intoxicating prose of which I was capable in which the visionary sequences would be written in the style of Hemingway. Admittedly, this didn’t quite work. The result, ‘A Perilous Ordeal’, was able to be salvaged using a slightly different technique.

A fairly trivial use of archetypal motifs can be deliberately employed to bring initiatory methods to the reader’s mind. One of them is to have one or more characters cross a boundary at a crucial moment. There’s something enticing about handling an event that has major significance in a particularly minor way. Jean Cocteau made liberal use of this sort of thing in his fiction, plays, and films. Crossing a boundary can represent the passage from one world to the next, or from one state of awareness to another.

Acts of trespass and other transgressions can be employed in a similar manner. These things have long been tied to the process of occult initiation. The myth of Orpheus stealing into the underworld to retrieve Eurydice is particularly poignant, as is the rebellion of the Angels depicted in the book of Genesis and the apocryphal books of Enoch among other places. The act of theft makes a frequent appearance in my work. Of course, Mercury is the God of thieves, and theft relates to the Promethean myth of stealing fire from Heaven. There are so many different ways in which theft can be tied to esoteric motifs that I find myself coming back to it again and again. In terms of dramatic tension, the act is endlessly adaptable.

Writing about specific occult techniques can be far more interesting when they’re shown outside of their usual context. I’m never content to write about these activities exactly as I actually practice them. I’d rather switch things up a little—have somebody astrally project into the wallpaper of an opulent hotel, for example, or conduct a complex rite employing mirrors, cigarettes, and a metronome.

Similarly, genre tropes not usually associated with the occult can be used to give a story a unique flavor and atmosphere. I’d like to see a wider range of occult fiction that employs a more playful approach, rather than adhering to the typical horror or gothic motifs. It’s always mystified me that occultism and horror are so often seen as synonymous. As an occult practitioner of 25 years, I don’t find it to be the slightest bit horrific. There are so many possibilities for a truly esoteric literature that it would take an army of authors to exhaust them—homages to the cinema of the French New Wave or to erotic Italian crime comics such as Kriminal and Sadistik; pastiches of Heinrich von Kleist, Robert Musil, or Georges Simenon; sadomasochistic locked-room mysteries; poetic epics intermingled with romantic sex comedies; or long, intoxicating monologues such as those found in the work of Clarice Lispector. I could easily imagine the basic narrative of André Gide’s The Counterfeiters reworked as a study of the occult application of Goethe’s theory of colors. The possibilities are endless.

Almost always, when starting a new piece, I find myself thinking ‘what would it be like if Ann Quin, Dorothy Parker, Tanizaki, Truman Capote, Marguerite Duras, Colette, Robert Walser, or Nabokov were to have written a blatantly occult piece?’ I can’t help but wonder, and find myself compelled to give it a try. Among the most important of all of my influences are authors whose work I haven’t read. There was a period before I’d read Patricia Highsmith, the author of The Talented Mister Ripley, during which, having read about her books, I’d created a completely fictitious literary output for the author in my mind. My anticipation of her work was so deliciously tantalizing that I almost couldn’t bring myself to read it. When at last I did, of course it was something of a disappointment. Her characters are a little flat and unbelievable, she tends to hit the reader over the head with the subtleties of the narrative, and her plots are not quite as intriguing as I’d hoped. The bright side is that there’s now a nonexistent Patricia Highsmith that exists for me alone and whose works I’m free to plagiarize. I haven’t even begun to exhaust the outermost layers of this source.

JUSTIN ISIS: In attempting this interview, I’m faced with the basic problem of wanting or needing to declare some kind of new literary movement, and while I’m more than capable of doing so, I feel that any sort of immediate genre tag, however novel, would do a disservice to your writing, besides basically failing to explain much of what it is "about." Along the same lines, I'm going to suggest that the "content" level of your writing is in some ways less important than, or is at least often subordinate to, its structural and process-based elements, including, presumably, your own private methods of conception and composition.

To state things clearly: we’re both practicing occultists, and we’re both engaged in projects which I feel veer closer to general “literary” writing than to any kind of genre material, while still not really resembling much of what would usually be considered literary fiction, due to their fundamentally different starting conceptions of reality. "Neo-Decadent" and "Post-Naturalist" are terms that come closer to accurately describing them, but even they don't fully express what we’re about, or the extent to which our writing begins from ontological assumptions that I'm fairly sure aren't shared by those currently in control of the mainstream publishing industry and its supportive apparatus of critics and academics.

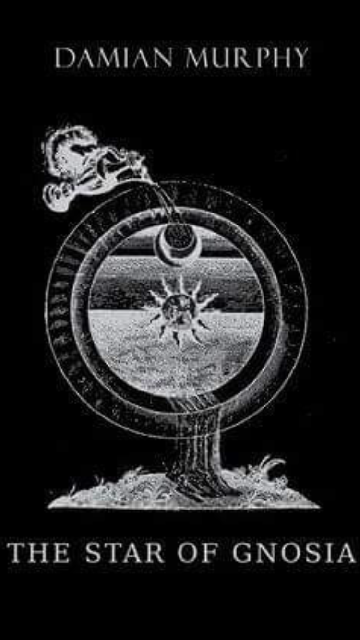

The problem here is that by saying something like "practicing occultist" or "decadent fiction," I've immediately but quite involuntarily stranded the casual reader in a swamp of outdated associations, stagnant and reeking with the accumulated deadwood of various "Weird" writings, vague and insalubrious Victorian ghost stories, the posturing of allegedly transgressive horrorists, and all kinds of other obstructive detritus which really has nothing to do with the reality of what he or she would encounter in your stories. So, for those who have yet to check out Daughters of Apostasy, The Star of Gnosia, The Academy Outside of Ingolstadt, or any of your other work, I'll do my best to rescue them from the murk: there is nothing remotely gothic, lurid, ghostly or satanic about your stories, which, to the contrary, often unfold in a spirit of conspiratorial joy and exploratory excitement. Rather than operating in a mystically ambiguous haze of undefined and possibly meaningless portent, your fiction is executed with an architect's eye for precise detail and structural integrity, and usually concerns characters with very definite, concrete ambitions, which just happen to involve areas of experience that have traditionally been termed "esoteric." The intensely spatial or perhaps cartographic nature of your writing—with its frequent emphasis on the interiors of imaginary yet plausible and easily-visualized apartments, hotels, churches and even automated rides—along with your tendency to conceal or at least obfuscate certain crucial pieces of information from the reader in a manner that nevertheless seems "fair," recalls writers like Robbe-Grillet, Nabokov and even Gene Wolfe, although I stress (again, for the casual reader looking to investigate) that your books don't really resemble any of theirs, and aren't in any sense excessively "demanding," despite almost exclusively concerning those aforementioned esoteric areas of experience.

As you've noted in another interview, we're not exactly inundated with credible occult fiction, much less any kind of broader cultural framework in which to consider it, even if it did suddenly come into existence. And this seems to have been the case for at least the past century, so that in terms of critical consensus, something like Graham Greene’s Catholicism might be tolerable for the “moral gravitas” it supposedly lends his fiction, but Yeats’s spiritual system and Golden Dawn membership can only be embarrassing anomalies to be explained away or ignored. A mystic like Machen can be dismissed as a “horror writer,” a mere precursor to Lovecraft, while Crowley’s fictional output can be ignored entirely. There's a persistent tendency to sideline these writers, all while holding up the most staid and unimaginative materialist Realists as the true purveyors of "serious" fiction. Can you explain why you think this is the case, or more exactly, why so few initiated writers have protested this shabby treatment? Note that by "credible occult fiction" I'm assuming you share my idea of it as fiction that results from direct experience of ritual work and is intended to offer or at least hint at some kind of gnosis through the act of reading, and/or fiction that is composed using the same mental and spiritual faculties involved in ritual or ceremonial work—rather than fiction that simply references spurious grimoires and arcane abstractions as stage dressing for a genre exercise.

DAMIAN MURPHY: One of the things I’ve tried to do is create a symbolic vocabulary of initiatic experience that hasn’t been used elsewhere. Given this as one of my starting points, it seems inevitable that I’ll end up creating something that doesn’t fit with conventional ideas of literature or genre fiction.

I feel like I should give some concrete examples of the motifs I’ve made use of in order to keep my answers from being too abstract. Among them are anonymity, theft, games of strategy and games of chance, aristocracy, and trespass. There are others. On the one hand, I try to make my use of these things as easy to understand as possible, while on the other I tend to switch up the underlying associations from story to story in order to keep these symbols fluid and organic in the reader’s mind. This is all put to the service of igniting an understanding that can’t be conveyed by purely descriptive means.

To elucidate this idea, I can talk a little bit about the use of theft in different contexts. "Seduction of the Golden Pheasant" opens with a party in an opulent chateau in which the guests are encouraged to steal something of value before the night is through—this act has repercussions both subtle and explicit that continue to unfold throughout the story. In "The Savants of the House of Exile" the spiritual aspirant is compared to a thief in the night, having stolen away with the perfection of the Absolute in their desire to know the unknowable. In "The Hieromantic Mirror" a pilfered game piece is used to affect a shift in the relations between a consulate and the embassy it represents. Each of these examples involves something essential about the act in question, yet each reveals a different facet of the jewel.

Occultism is so often associated with the horrific in film and literature. I want to portray it in the light of my own experiences, which tend far more toward exploration, strategy, revelation, and luxury (if not necessarily in the material sense). I’m very happy with “Conspiratorial joy” as a descriptive term for my work. On the one hand, I want to present the reader with a mystery that’s impenetrable yet able to be explored, while on the other I want to make them feel that they’re part of the exploits of the characters they’re reading about, that they’re able to get away with something that they might not otherwise allow themselves to experience.

To give another example, in “The Scourge and the Sanctuary” a young woman forces her way into an abandoned penthouse for no other reason than to indulge in the act of occupying the space. I want to allow the reader to indulge, to the greatest degree possible, in the perverse pleasure of committing a minor transgression. This all ties back into the occult themes of the work. The esotericist is no stranger to crossing boundaries and exploring things that are forbidden to them. By mingling the esoteric with a relatable experience, I hope to convey an impression of what it’s like to participate in an initiatory process.

You’ve cited mystical ambiguity, which is one of my main points of frustration with so much of occult literature. Another lies in refusing to step outside the bounds of official occult history. M.R. James was very fastidious about this, and a lot of occult writing tends to follow his lead. I don’t think this necessarily has to be a bad thing, it’s just not at all what I want to do. I would much rather create a piece of writing that the reader feels free to explore on their own terms than to provide an academic illustration of some aspect of esoteric lore.

On the other side of things, I think the reason that occult fiction has been so downplayed is that it has largely tended to be self-consciously rooted in the domain of genre work. Even Crowley’s more occult-oriented fiction tends to come off as inauthentic and even campy. His best stories consists of realist narratives like “The Stratagem”. Orders like the Golden Dawn tend to get lumped in with things like Theosophy and the spiritualist trends of the period. I think more hope might lie in outlying practices and individual approaches to initiation, as well as bridging the gap between purely human experiences and those of the aspirant on the path of initiation. I can imagine an esoteric version of Good Morning, Midnight, written with all of the pathos and complexity of Jean Rhys’s classic novel, yet replete with initiatory themes and motifs.

As an aside regarding Gene Wolfe, whose New Sun books are a tremendous influence on my own work—at some point, he started producing novels that resemble crossword puzzles. These later books don’t quite capture the poetry or mystique of the New Sun series, yet they do have a certain attraction insomuch as they seem to comprise the kind of puzzle one might find within the pages of a newspaper (though, of course, far more complex). When I was very young, I used to be fond of the "Two-Minute Mysteries" series—little one or two-page narratives in which a mystery was presented that the reader must try to solve using the clues provided in the text. Wolfe's post-New Sun work brings these to mind, combined with what might result if one were somehow to superimpose every branch of a Choose Your Own Adventure book into a single line, all processed with a clinical eye for technical detail. I can't help but be strangely fascinated by this.

I’m happy to read, in the question above, that my work doesn’t come off as too demanding or difficult. My aim is to produce prose that reads like a fever dream of an opiated trance, gently ushering the reader from point to point without the slightest bit of friction. Elaborate settings are a big part of this. I take a number of approaches to this aspect of the work. One of them is to try to recreate the setting of a particular artwork that strikes me in a certain way, then to alter it according to various criteria. I’ve done this a lot with the paintings of Remedios Varo among others. In doing so, I get the benefit of exploring these spaces in a very different way than I have before, and of picking up a thread that’s been laid down before me and developing it further. I spend a lot of time mentally inhabiting these spaces. There is in this a very conscious elaboration of the talismanic art.

As for your assessment of "credible occult fiction"—yes, absolutely. I think it’s definitely possible to reveal aspects of occult gnosis through writing and I’ve continually attempted to do so in my stories. I don’t view these experiences as necessarily the exclusive purview of the practicing occultist or initiate. Initiation allows for the completion of certain processes that are unlikely to take place otherwise, but the attendant exaltation of consciousness, the elevation of point of view, and the direct perception of particular mysteries are experiences that can be had by a wide range of people in a wide range of circumstances. This can be done without the slightest betrayal of “occult secrets”, which are specific either to particular groups or particular operations.

JI: As previously stated, one of the things that absolutely has to die in the 21st century is the belief that "materialist humanism" is somehow the default position of "serious" literature, and that a kind of recalcitrantly shallow journalism must of necessity underlay all such endeavors. I don't believe that the omphaloskeptic complacency of a David Foster Wallace or Zadie Smith mindset is best suited to grappling with the highly symbolic correspondence bases of late capitalism; if anything a Kabbalistic mindset seems more appropriate to the task. With that said, thanks to the Internet, chaos magick has in recent years had something of a pop resurgence, while various older magickal texts are more freely available than ever to the solo practitioner, and the lodges of more traditional orders are better able to communicate globally. Alongside all this, figures like Robert Anton Wilson, Genesis P-Orridge, Grant Morrison, Carl Abrahamsson and others have done much to pave the way for a kind of global Occulture. I'd argue that we're still in the early stages, though, and that the various disciplines, traditions and perspectives being synthesized at present still haven't really cohered into anything like a shared cultural base that could give rise to the kind of fiction we desperately need. Your writing seems to me to be at the forefront here, and so the question becomes—is this even something that SHOULD happen? Occult means "hidden," after all, and obscurity has its own pleasures. It'd be dishonest to deny the appeal of an elite audience of sophisticates, but my own position is very much "lay claim to the fictional mainstream." I'm interested to hear how you feel about this, though, and how you think it could possibly develop. Can you imagine what a general Damian Murphy-influenced art and writing scene might be like, and what the wildest far-future consequences of such an outcome would be? For example, if fairly unintelligent teenagers in the future began reflexively copying your writing style and fictional concerns without any real understanding of, or interest in, the background and life circumstances that led you to develop them: also what you envision such an "inauthentic" mass-copying of your approach might look like in related fields (film, music videos, mobile games, etc.)?

DM: For whatever reason, I have a kind of blind spot in regards to groups of people, movements, scenes, and cultures. I seem to have been designed to navigate the world almost exclusively by way of anomalies and exceptions. I can see the need for a kind of occulture, and would even be happy to contribute to it, though I can only ever see myself operating outside of it. Seeking out and finding things that are obscure or hidden is something that comes very naturally to me. That said, I do take steps to try to expand my writing’s readership as much as possible. I definitely don’t intend to keep my work deliberately obscure.

While I can’t quite envision how my work might fit into a larger movement, I have given quite a bit of thought as to how it might be put to use outside of the confines of conventional narrative. My stories are anything but instruction manuals, yet there are other possibilities. I often try to create a kind of complex Sufi parable, something vaguely akin to the “Two-Minute Mystery” pieces referred to above. By taking the time to delve into the text and solve the mystery (insomuch as a single solution exists), one might find something of genuine worth that can hopefully be applied outside of the context of the story.

I’ve written pieces in which narrative texts are put to use for a variety of occult or religious purposes—as oracles, keys, prayers, navigational devices, or simply as a means of contact with the invisible. My work often reaches toward embodying this kind of thing itself, though it’s important that it retains the ability to be read purely for enjoyment. Whatever utility my writing might have would be lost if it was not compelling for its own sake.

I like the idea of laying claim to the mainstream. It would be bad strategy to assume that the ideas and techniques behind our work could never find a large audience. I don’t think that popular acceptance necessarily stands opposed to obscurity—I think it’s possible to have the best of both worlds. Things that are truly hidden remain hidden no matter how much attention is placed on them. There are states one can attain through occult practice, for instance, that, though a wealth of written material is available regarding them, are still very difficult to actually get to and are consequently truly known to few. I think it’s possible for a person’s work to gain widespread popularity and yet retain a very inaccessible core.

As to what it would look like were my work to have a larger impact, I find myself descending into pure fantasy whenever I try to visualize that kind of thing. Inauthentic appropriations of my fiction could work very well in the context of electronic gaming. I could see “The Star of Gnosia”, “The Ivory Sovereign”, or “The Scourge and the Sanctuary” working perfectly as Nintendo-era games, while “Abyssinia” might make a fitting Atari 2600 demo. It would almost work better if a relatively shallow approach to the stories themselves was used, appropriating some of the imagery without necessarily making reference to the ideas that lay behind them. I would be beside myself with joy if somebody were to actually do this, or if I went to the Ghost Box website and saw that somebody had created a soundtrack for “The Imperishable Sacraments” or something.

Appropriating material into what seems like an inappropriate medium is an art form in itself. Several years ago I began a project in which each of the 18 chapters of James Joyce’s Ulysses was re-interpreted as a 2600 game. The whole series was intended to serve as a Kabbalistic exegesis of the book. My thought was that somebody else could do the same thing for the Catholic side of the text. I gave up on the project when I realized that, were I to pay the book its full due, it would end up consuming the rest of my life. While I love the idea of devoting one’s life to something so deliciously outré, there were other things I knew I’d want to do that were probably more important.

JI: Along those lines, some of your most strikingly original stories are those like “A Mansion of Sapphire” and “A Book of Alabaster,” whose plots unfold from lengthy descriptions of imagined gameplay in fictional console titles, specifically those on the now-retro ZX Spectrum and Atari 2600. The only other example of this technique that comes to mind is the relatively obscure novel Lucky Wander Boy by D.B. Weiss, who mined the idea for some vaguely philosophical effects, but with nowhere near the level of textured exploration present in your stories, where the sustained mental effort of following the characters’ progress becomes something like an occult meditation or visualization technique, especially given that the sumptuous descriptions—packed with complex sensory details—would seem to be impossible, given the hardware limitations of the systems in question. And yet, reading these stories, it occurred to me that this was in fact how a child playing these games would experience them: as discrete and completely immersive worlds, rather than the primitive tableaux of crudely pixelated sprites that appear to adult gamers. And this brings me to a triangulation of sorts that I’d like to suggest has relevance to your work: video games, psychedelics and the occult, particularly as they pertain to “the topology of the ineffable."

Looking back, much of the more respected 20th century literature was preoccupied with time and how to depict its passage, along with related issues of the telescoping of memory. Proust, Woolf, Powell and Ballard are obvious examples. In contrast, your work seems much more preoccupied with space, and the way the mind constructs and organizes it. This “production of space” theme seems especially present in “Permutations of the Citadel,” an incredibly complex story in which, by making alterations to a map of a hotel present within the hotel itself, the characters are able to alter the building’s architecture, through which they can access a kind of reverse-reality filled with fictional and mythical archetypes, with the final aim of reaching an impossible inner room. Apart from being an exploration of the interpenetration of fiction and reality, this story seems to be at heart a literary instantiation of the map editor function present in countless video games. What it and the other stories just mentioned have in common is the idea of the macrocosm contained within the microcosm—that the Absolute can be present within a model or representation produced through magickal means. This seems to relate to the technique you mentioned of “translating” one fictional medium’s content into a different medium.

I'm reminded here of other recent “transforms” in things like the Petscop series of YouTube videos, which is in essence a creepypasta story about a haunted PlayStation title translated into the medium of constructed video game footage and its accompanying commentary, amounting to a kind of Alternate Reality Game—almost the opposite “transform” to the stories of yours dealing with lengthy descriptions of fictional games. Despite its status as a series of online videos, Petscop is clearly a literary narrative, with a questionably reliable narrator and much implied backstory to be read between the lines, and its ongoing storyline makes more sense when read as literature than it does as a film or even a standard web series. It strikes me as the pioneer for a new kind of narrative. Now, with the concurrent rise of VR and AR technologies, we seem to be experiencing a lack of any clear separation between online spaces and those of our everyday physical landscape, and it seems to me that childhoods immersed in video game worlds were fairly apt training for the current state of multiple interpenetrating realities, as well as preparation for the other realms of experience accessible through entheogen use, astral travel and other traditional occult techniques. Do you see fiction as being a means of constructing a macrocosm-housing microcosm, and if so, do you see digital spaces as being merely one part of a spectrum that extends through more conventionally immaterial realms? I’m curious as to whether you feel that video games, psychedelics and the occult are overlapping technologies, or even aspects of the same thing. If this is the case, then are there any other elements or influences that have led you to take this fictional approach?

DM: One thing that still fascinates me about older computer and console games is their tendency to convey a distinct sense of place. Modern electronic games do this by creating environments that more or less resemble our own (so much so that, after spending even a short amount of time playing them, I need to go outside and gorge myself on visual stimuli to recalibrate my senses back to physical textures). Older games are much more abstract, and hence are capable of granting access to far more curious feelings and associations.

There are games I remember playing in the early 1980s that conveyed a sort of genius loci that remains with me to this day. Sabre Wulf comes to mind with its jewel-like forests and charging pink rhinos. These feel every bit as vivid as the physical locations I remember visiting in my youth. I occasionally dream of these environments, often in completely different settings. The derivation of a sense of place from an abstracted symbolic environment seems directly tied to the prospect of accessing visionary spaces using cryptographic sigils and holy names (among other things).

“A Book of Alabaster” brings another element into play—nostalgia. One of the things I was getting at with this story is that, while nostalgia is necessarily delusional, that doesn’t mean it’s wholly without worth. I don’t think we really remember the feelings associated with our past experiences. I think the feeling of nostalgia is something new, created in the present, which our brains tend to associate with particular memories. By exploring nostalgic feelings with the assumption that they have nothing to do with anything that actually happened, I think it’s possible to find aspects of the self that were previously concealed. Of course, it’s necessary to avoid falling into the trap of chasing after the illusion of an ideal past.

Spatial experience became an obsession for me in the early 2000s when I finally managed to access my capacity for visionary experience. It took me quite a bit of work to do this. I underwent fairly conventional esoteric training over the course of nearly a decade prior to that time. The gates of astral perception were very stubborn in my case (despite all of my earlier experience with psychedelic substances). When they finally burst open the trickle turned into a flood more or less overnight. Every aspect of my life changed very quickly after that. It was as if I’d found my true vocation.

There is a very human tendency to spatialize every aspect of experience. Henry Corbin writes extensively about this in terms of religious experience, particularly in The Man of Light in Iranian Sufism and Temple and Contemplation. With the idea of spatiality comes that of orientation, which is a key I keep returning to throughout my work. Physical orientation and symbolic orientation are intrinsically linked. While the former is needed in order to navigate the outer world, the latter is needed in order to navigate the subtler planes. Symbolic orientation comes into play in a number of stories—“The Imperishable Sacraments”, for instance, with the traversal of the southern star which guides the main character from one place to another. In “The Savants of the House of Exile” the interface between the two sides of the mirror (so to speak) is explored in terms of orientation within Piranesi’s labyrinthine prisons.

There are overlaps between video game environments, occult activity, and psychedelic substances, though they’re each so distinct that I think it’s worth paying as much attention to the differences between them as the similarities. I wouldn’t say that they’re different aspects of the same thing as much as they tend to refer back to some of the same things. Orientation, for example, can be a part of all three of them. When I was 15, I found, upon ingesting LSD, that I could perceive the winding streets of my neighborhood as if from a birds-eye view while I was walking through them. Before that, I’d never quite grasped how they were all connected.

I remain somewhat militant and traditional when it comes to occult practice. I don’t think that ingesting a substance can ever reproduce the cumulative effect of a regular discipline. A video game, on the other hand, could theoretically be as immersive as a dream or astral vision, though there are particular laws to which the latter two adhere that a human-created environment would be unlikely to capture.

Orienting oneself in a video-game environment, of course, is a huge part of the experience, necessitating endless maps and navigational strategies. One of my favorite books when I was a kid was a compendium of game walkthroughs entitled The Book of Adventure Games. At the time (the mid-1980s), I owned about one third of the games documented in the book—text-based games, dungeon crawlers, several precursors to the point-and-click adventures that gained in popularity a few years later. I became obsessed with the maps for games that I’d never played. I’d study them, try to imagine what they referred to, create maps of my own with the sole intention of making them as intriguing as possible.

This, in part, has inspired a technique that I’ve used in some of my longer novellas. I’ll create chapter headings first without having any idea what they might refer to, then write a story that conforms to them. A certain amount of editing and rearranging as the piece is composed is always necessary. “A Spy in the Panopticon”, among other stories, was written in this way. This is also partly inspired by some of the early French and American film serials—films like Les Vampires, Judex, The Exploits of Elaine, and The Hazards of Helen. The titles of the episodes of these films are so evocative that they could almost comprise an artwork in themselves.

JI: I had a similar childhood obsession with video game strategy guides, often those of games I never ended up playing. In fact I essentially learned to read from things like Jeff Rovin’s How to Win at Nintendo Games series (a slightly later analogue of the “Book of Adventure Games” you mentioned), and after that I engaged with screenshot-heavy guides like Secret of Mana by Rusel DeMaria as if they were graphic novels rather than mere manuals for the games themselves. I’ve often thought this “strategy guide comic” format would be an interesting avenue to pursue, along the lines of Petscop. There’s really limitless freedom with this kind of thing and I’m surprised that we aren’t seeing more crossplatform hybrids springing into existence.

And I suspected you were doing the “create chapter headings first and come up with the story later” thing, because I do it a fair amount myself. In some cases I’ve held onto particular titles for years before finding anything appropriate to do with them. You also make use of what I’m forced to term “concept album subdivisions” — dividing a larger story into numerous individually-titled sections, with characters and events that sometimes don’t seem to overlap at all, until the greater design emerges on later reflection.

I’d risk saying that we’re both “top down” writers — in other words, the structure or formal armature of what we write is as important as the “content” (or IS the “content”), and our creative process is likely different from that of writers who seem content to dick about with unfocused drafts, character outlines, logorrheic overwriting/cutting (binging and purging?), and all other time-wasting practices suggested by the workshop industry. I suspect that a large percentage of currently active writers are ineptly screening imaginary films in their heads and then doing their best to transcribe what they “see.” This is in line with the emphasis on what to my mind is the most boring possible “transform” — a book into a film/TV series (there now seems to be little difference between the two). Because the hinge here is the idea that literary art aspires to the condition of dramatic performance or filmed theater, and I’ve never wanted to be a dramatist, much less a screenwriter. But the idea that a story or novel is more like a poem, a building or a drug than it is some kind of episodic visual narrative doesn’t seem to be especially common, though it’s one I wish was more influential, if not just because it would spare us the soporific supply of little word-prompted mental movies that pass themselves off as important novels.

With that said, in your opening piece you noted the use of more oblique filmic and game influences on your writing. I’d emphasize that you almost always employ the techniques you mentioned without drawing attention to them. This is in contrast to the amusing yet more crassly transparent approach of OuLiPo or some other “experimental” writers. Your writing always seems polished and “seamless,” despite being by your own admission process-based or rooted in consciously-chosen conceptual frameworks. To my mind, this kind of approach is an absolute necessity for modern writing, and demolishes the need for any of the cliched and outdated vocabulary of “character development,” the artificial “story vs plot” distinction, etc.

Anyway: to expand on an example you gave, the boxed set A Spy in the Panopticon comprises a suite of stories and novellas published as several discrete booklets, chapbooks and fold-out inserts. None of the fictional pieces contained therein are overtly connected to any of the others, but when taken together they function as a sort of fictional hyperobject with recurring images, themes and motifs, pivoting around ideas of hereditary magickal power, obscure “matriarchs,” spyholes, objects such as cameras and lenses, notaries and other official functionaries, etc. In the title novella, the main character makes use of these devices to write her own novel, one with the same name as the story she inhabits. It’s the sort of thing that would seem obviously and irritatingly recursive, were it not for the deeply strange, textured prose and almost 60s-psychedelic mood. It feels like the central work around which the other stories in the box set orbit, each of them offering a different key to the meaning of the overall work. Apart from its unique physical presentation, which really deserves more descriptive justice than I’m doing it here, A Spy in the Panopticon seems like the benchmark for what we could call the Cubist novel or object-oriented plot, one based around a constellation of images and motifs rather than recurring characters. There’s a submerged internal logic here, one open to multiple permutations, as there is really no fixed order in which the pieces need be read. As with the pre-chosen chapter headings, did you explicitly start with a list of objects and motifs that you treated like game pieces, developing the stories from their interactions? Are you planning any future works along these lines, and can you think of where such expanded fictions might go next?

DM: A Spy in the Panopticon, as a boxed set, was put together without any overt regard to theme, though I wrote all of the pieces in it during the same period (with the exception of “La Fleur Infernale” which was written for the William Blake anthology All is Full of Hell). They definitely feel of a piece now that I look back on them. I’ve long had a tendency to hide clues to one story in other stories, and this kind of thing is not absent within the pieces in the set.

The story “A Spy in the Panopticon”, aside from being based on the chapter titles, definitely started with a collection of motifs and aesthetic cues. Game pieces comprise a good metaphor for the way in which in which I’ve developed the different aspects of several of my stories. I often end up moving sections of the narrative from one place to another, switching their order and swapping set pieces and key phrases. There’s a very particular internal logic that each piece must adhere to. As the story progresses, the pieces all begin to fall into place, usually with a little rearranging. By the time it nears completion, if all goes well, the different facets of the narrative flow together like a seamless whole.

My desire is in no way to construct what looks like an experimental story with this process, but rather to create a fairly traditional narrative that has a clear sequence of events, yet which harbors a complex, self-referential structure that functions as a system of internal mirrors. The book that’s written within the story “A Spy in the Panopticon” could be taken as a sort of parody of this process.

“A Spy in the Panopticon” is a little bit along the lines of the elaborate crossword puzzle that I mentioned above. A second narrative is concealed behind the parts of the story that are shown openly. My hope is that the hidden layers of the story will resonate on some level with even the most casual reader, providing a degree of depth that can be accessed with no effort on the reader’s part, but which rewards whatever effort they put into it.

All of my work is intended to make the reader desperately want to know more and to return to the narrative in the hope of finding it. There’s a delicate balance between creating a desire to understand and satiating that desire. If the narrative provides too many questions without enough answers, it tends to lose the reader’s trust—they’ll think the author is merely bluffing and that the answers don’t exist. To resolve every question in the reader’s mind, on the other hand, is to go too far. There should be a deficit, in my opinion, at the end of every piece of fiction—a number of things the reader still doesn’t know or can’t quite understand. This deficit is like a door left half-open. It allows the reader to explore a piece on their own without having their hand held by the author. Ideally, there should be a feeling that a deeper understanding lies just around the corner, that it will all become clear with just a little more examination. Of course, there needs to be a certain amount of truth to this. When a reader comes back to look for more, they should be rewarded not only with some answers and additional layers of depth, but with further questions as well.

JI: Much of your work has been published in lavish, opulent, ornate, lapidary, etc. editions from Ex Occidente/Mt. Abraxas. These editions go beyond mere hardbacks and are incredible works of art in themselves, with complex illustrations, dust jackets and frontispieces, high quality paper and bindings, and formats that often exceed the standard dimensions of most commercially-available fiction books. In the case of the recent Abyssinia and Psalms of the Magistrate, and your editing project The Gift of the Kos’mos Cometh!, it’s safe to say that even if the text inside were random gibberish, the books would still present considerable visual and tactile engagements worthy of serious time investment. With that said, how important do you consider this mode of presentation to be to the reading experience and reception of your work, and do you find the increasing popularity of these editions to be a reaction against Kindle culture and the kind of e-books-as-default mindset that took over in the last decade? I don’t want to waste time rehashing the “death of print” debate, which was tedious from the start, but it’s safe to say that these productions (and the editions of other imprints like Zagava) have pushed book design forward at a time when people seem to increasingly take it for granted that “book” refers to a file on an e-reader. My sense of reading these works is that their physical heft, texture and overall material quality greatly contributes to the reading experience, if not just because you can’t easily take them on the train or stuff them into a jacket pocket, much less flip through them in between browsing social media sites and checking text messages. For the most part, I don’t care whether people read my books in ebook or print, but I’d resist ever switching entirely to the former, as my desire to write is in large part a desire to produce physical objects, and when it comes to non-standard text layouts, I find the ebook medium to be fairly unsatisfactory for representing things the way I want. My only concern is that the limited print runs and high prices of many of your books will correspondingly limit their audience. Do you think this is a problem, and what do you see as the future direction of book production and consumption, particularly that of your own work?

DM: The format of a book has a big impact on the way the text is taken in, but I don’t necessarily think that the experience of reading something in an opulent hardcover edition is better than reading it in paperback. Different formats each have their advantages. The most important thing is probably the typesetting, font, margins—all of the things that most readers don’t consciously notice but which very much affects how they respond to the text.

So far, I’ve been lucky enough to be able to reprint my earlier stories in definitive editions that are more generally available. My hope is to continue with this, eventually making everything available in an affordable, paperback format. One part of me likes the idea of having a lot of disparate pieces of writing in different places, some of which are nearly impossible to find, while another part of me is attracted to the idea of having a series of collected works that includes absolutely everything. While I ultimately lean toward the latter, I currently seem to inhabit the best of both worlds.

I don’t have a problem with electronic formats, but, like yourself, I prefer to produce a tangible object. There are entire categories of experience that are, if not eliminated, at least drastically altered with electronic reading devices. Aside from a physical manifestation, a book can also have a more tenuous component. More than one modern publisher (specifically of occult books) claims that each of their releases has a particular spirit behind it. In Mao Shan Taoism, there’s a type of book that exists in two places at once—on the physical and in the invisible. Part of the process of mastering the techniques revealed in the book involves bringing its two component parts together, which requires a certain degree of attainment. I think it’s very natural to regard a book as a talisman and to conceive strategies by which its function as such may be furthered. On the other hand, it seems likely that this kind of thing will start to occur with electronic formats as well. It probably already has.

Books as physical objects have their drawbacks as well. Too many physical possessions can lead to the same type of desensitization as reducing one’s experience to a handful of devices. You can only pay attention to so many things before quality starts giving way to quantity and literary pursuit becomes a kind of gorging of the intellect. I still read a fair amount of fiction, though I find, as I get older, I tend to read far less books on the occult, religion, and the initiatory mysteries than I used to. When I was younger, I tried to read everything that I could find, so long as it concerned my areas of interest. In recent years, I keep coming back to a handful of essential sources and allowing myself to go deeper and deeper into them, finding threads within them that require a more meticulous and prolonged study to catch.

JI: In line with the current ongoing Neo-Decadent reformulation of everyday life, you’ve tasked yourself with producing the Neo-Decadent Manifesto of Occultism. Without necessarily recapping the entire work, can you give a brief outline of where you see the Current heading, especially as it pertains to future writing? To my mind, besides the aforementioned occult/game stories, the territory I’m interested in seeing you explore further is best represented by “The Immaculate Scrambled Automat” in the upcoming Neo-Decadent Cookbook, which verges on science fiction, and especially “The Eroto-Comatose Automaton,” perhaps your most conceptually violent and intricate piece. In the latter, there’s a long scene where, as part of an escalating magickal battle between two warring brothels with opposed ritual systems, the protagonist improvises a public ceremonial offensive over the course of several hours, folding in cues from her urban environment in the manner of a Situationist dérive, recruiting strangers as participants and working in all kinds of seemingly random signs and inputs. Besides bringing to mind Mandaean eschatology, Communist kitsch, bureaucratic absurdism, the aesthetic of German New Objectivity, 1960s retro-futurism and more recent hauntology, it reminded me of Joel Biroco’s “juxtapositional magick,” and the relatively underknown novel The Adventuress of Henrietta Street by Lawrence Miles. Are you planning any other stories in this vein, and how do you see it interacting with the overall styles and themes of Neo-Decadent fiction?

DM:“The Immaculate Scrambled Automat” started out as an attempt to capture the atmosphere of a particularly vivid dream I’d had several months before writing the piece. I woke from the dream thinking “I have to somehow make this into a story”. A number of additional elements fell into place in the writing—retro-futurism, hauntology, and classic fetish imagery, among other things. These were all put to the service of elucidating the feeling that arose from the original dream. The piece is very short—less than 1500 words—which is uncharacteristic of my writing. I’d like to write more pieces along these lines. We’ll see which way the muse takes me.

It feels like there are so many different directions in which Neo-Decadence can go. I’d like to see some of the more peculiar aspects of the aesthetic landscape of the 20th century adapted into its mystique. This is kind of what I was trying to do with “The Eroto-Comatose Automaton”. I had in mind a number of different visual influences—Soviet-era Russian film posters, the S&M photography of Ellen Von Unwerth, the themes and motifs of early DEVO—and had a very strong idea of what I wanted with the end result. I spectacularly missed the mark, yet, as so often happens, I managed to create something that I could never have planned.

I’ve found this type of aiming and almost intentionally missing to be incredibly fortuitous. I read somewhere that Throbbing Gristle once tried to create a perfectly normal rock song. They’d originally titled it ‘Hit by Rock’, but ended up renaming it ‘Hit by a Rock’ after determining that the resulting piece of music sounded like nothing else ever recorded before. There are few techniques more effective that getting it wrong.

JI: As is customary at the end of an interview, can you suggest any books, films, artworks or pieces of music that you consider to be important, either representative of where writing and art are “at” at the moment, or where you would like to see them go (these don’t have to be works released in the 21st century, although I’m interested in what current productions interest you now)? I’m thinking here about what might be some of the cornerstones or building blocks of a new occult-infused Post-Naturalist approach to writing. And I’m particularly interested in the “handful of essential sources” you mentioned, that you find yourself going deeper and deeper into as the years pass.

DM: The first authors that come to mind are yourself, Quentin S. Crisp, and Brendan Connell. M. Kitchell has been putting out some very interesting work, as has Andrew Condous, though the latter’s books are all out of print and hard to come by at the moment. Jane Unrue’s book Love Hotel is extremely compelling. I’m very much inspired by her approach to both prose and narrative, though I can’t imagine anybody being able to reproduce it. There’s a temptation to just keep naming recent authors I like, which would quickly become exhaustive. Berit Ellingsen is very good. As is Kristine Ong Muslim. Both of them may have had a hand in inspiring “The Immaculate Scrambled Automat”.

I should mention Jane de La Vaudère, a 19th-century decadent author, just recently translated through Snuggly Books, whose prose I’ve become obsessed with. The strange thing about this author is that I like everything except for the occult sections of her fiction. As soon as she starts writing about occultism, my eyes glaze over. This well may be professional jealousy! I feel the same way about Balzac, whose Séraphîta I find intolerably dull (despite the fact that I name-drop it in one of my stories).

As for comics, there’s so much interesting work coming out now that it’s impossible to keep up with. A lot of people are doing interesting things with the Risograph copy machine. Le Dernier Cri is like the Ex Occidente of disturbing underground comics. Artists like Mat Brinkman, Julia Gfrörer, Tetsunori Tawaraya, Eamon Espey, Theo Ellsworth, Daria Tessler, Paqaru, and Igor Hofbauer have been putting out the kind of work I’ve been dreaming of ever since I first discovered underground mini-comics in the late 1980s. This is just the tip of the iceberg. I manage to find interesting new comic artists literally every week.

I feel like music has advanced ahead of writing by leaps and bounds, with the caveat that none of this applies to mainstream music. At some point, people started making music that incorporates wildly disparate influences—giallo themes, Ethiopian jazz, musique concrète, distorted AM radio-style soft rock, even things like Chinese opera and liturgical chants. All of these styles could conceivably be found in a single song. This has been going on since at least the 1970s, but it really ramped up in the late 1990s. I’d like to see more of this kind of thing applied to writing, especially if executed by a skillful hand. Your story “M-FUNK VS THA FUTUREGIONS OF INVERSE FUNKATIVITY” provides a perfect example.

As an aside, I keep hearing people in my generation lament the “death of underground music”. I can’t imagine what they could possibly be talking about. There’s more interesting underground music coming out now than there has been at any other point in my lifetime. I think a lot of people fall prey to a “the glory days are over and nobody will ever have experiences as authentic as the ones I had in my youth” mentality. They’re missing out! The glory days are unfolding right before them and all they can do is complain that nothing is happening anymore. One would be advised to avoid commercial radio, but when wasn’t that true?

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the films of Guy Maddin, whose influence has found its way into my work. His latest films, The Forbidden Room and The Green Fog are beyond belief.

The sources referred to above that I find myself endlessly coming back to include the works of Henry Corbin, the Neoplatonists as well as modern neoplatonic philosophers such as Algis Uždavinys, the Theurgy of Iamblichus, and Aryeh Kaplan along with the Kabbalists he so eloquently documents (who, like Iamblichus, are more than a little influenced by Neoplatonism). Jake Stratton-Kent has been publishing extremely compelling work over the last decade or so. His Geosophia provides a perfect contrast to the Neoplatonic thread that I draw so much from. These influences show up all over my fiction.

The Greek Magical Papyri, compiled and translated by Hanz Dieter Betz, is as essential a source as one could hope for. Within its pages can be found traces of theurgic approaches that seem to pick up where modern occult orders like the Golden Dawn have left off, though of course they’re much older. Certainly the Rite of the Headless One (PGM V.96—172), which was adapted by S. L. MacGregor Mathers as The Bornless Rite and used extensively by Crowley, provides a way forward for those that find themselves frustrated with the limits of Victorian occult orders. People have argued that this is little more than a rite of exorcism, but the god invoked is general enough to make the ritual more than suitable for a variety of different ends. This rite is merely one among innumerable examples. I could easily spend the rest of my life exploring and developing material from that one source alone. This is true of so many things—not the least of which are the Enochian records of John Dee and Edward Kelley.

I should add, as a final note, that I’ve just finished a novella that takes The Headless One as its central motif. It’s titled “The Acephalic Imperial” and should be released either in late 2019 or early 2020.

___________________________________

BUY DAUGHTERS OF APOSTASY

BUY THE STAR OF GNOSIA

Oustanding interview. This is inspiring and timely for me! I had just started reading Gnosia the day before this was posted. Not a coincidence, methinks.

ReplyDeleteSo good, I know I'll be coming back to this interview as I did with a handful of others that I read some time ago to artists that I love as Coil or Tg. It confirms some theories I had about this author about his unconventional approach to occult but there are so many infos here and also so many hints for future researches... I am glad to hear that he likes the idea to collect some of his works that are now out of print. Best interview I read in a long long time... Plus that cat is beautiful

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete